The 50-year-old man standing by his patch of paddy field in Campbell Bay exudes none of the calmness of the blue sea surrounding the Great Nicobar, the southernmost island of the Andaman & Nicobar archipelago. Sunil Kumar recalls the time his father, an ex-serviceman, left what is now Uttarakhand to settle down in the island in the 1970s. “It took him years to adjust to Nicobar, far from the hills of his home, and he struggled to cultivate his farm here,” recalls Kumar, who has taken over farming their land from his ailing father.

In the late 1960s and ’70s, ex-servicemen from the mainland were given land deeds by the Indira Gandhi government to settle on the isolated island, inhabited only by indigenous people belonging to the Shompen and Nicobarese tribes and facing threats from neighbouring countries and poachers. About 330 families were settled as part of the drive. “Then poachers from Indonesia and Malaysia, which is just 40 nautical miles away, would reach the shores and hunt the endangered wildlife,” says Tarun Karthick, editor of the news portal Nicobar Times. To make a living, Kumar also works as a driver for tourists and officials visiting the island. The southernmost point of India, the Indira Point, lies at the tip of Great Nicobar.

“However, very few people come here due to lack of commercial flights,” he adds. All this might change soon. The Ministry of Environment & Forests (MoEF) has approved a mega project, worth `72,000 crore, for the “holistic development” of Great Nicobar. To be implemented over the next 30 years, the project involves developing an International Container Transshipment Terminal (ICTT), a greenfield international airport, a township and a power plant. These would be spread across 166 sq km of the 910 sq km island. The project — conceptualised by NITI Aayog, and overseen by the Home Ministry as it involves a Union territory — will change the remote, secluded island to a global tourism and shipping hub. It fails to enthuse Kumar, though .

“Our lives will not be the same. If we are shifted from Shastri Nagar, which is part of the proposed airport site, we will have to start from scratch. People are saying our earnings and land rates will increase manifold. But the very thought of shifting is making me nervous,” he says. The 2004 tsunami had devastated the island and the people had to rebuild their lives and livelihoods. Less than two decades later, do they have to do it all over again, he asks. Before the tsunami, the islanders used to cultivate quite a bit of paddy. “After the tsunami, many shifted to cultivating coconuts, fruits and vegetables that, again, took time. If we are asked to vacate our land for the airport, we will have to start again,” says Kumar.

The Great Nicobar is strategically located. Almost 80% of oil that China imports comes from the Indian Ocean region. Over 300 Chinese vessels pass through it every day. Also China has been surveilling India through its ships in the region. We can’t leave such a strategic place as a mere fishing village. That’s why developing the island is crucial”

– SRIKANTH KONDAPALLI, Dean of School of International Studies & Professor of China Studies, JNU

THE ISLANDERS

According to Census 2011, 8,367 people inhabited the island, including about 200 Shompens and around 1,000 Nicobarese. “The current population, however, must be around 4,500 due to large-scale migration to either Port Blair, which is over 500 km away, or the mainland. People don’t get good prices for their produce. Poor earnings and lack of industry and jobs are forcing people to move,” says Karthick, whose maternal grandfather came from Varanasi as part of the 1970s settlement drive. “Now many people are hopeful that with this huge project, their lives might change for the better,” he adds. The project is expected to create 2.6 lakh jobs over the next 30 years.

Connectivity is key to the development of the island. To reach Great Nicobar, tourists have to now go on a more than 24-hour sea voyage from Port Blair or hop on one of the few helicopters. An international airport will improve connectivity and open the island up to tourism. It will also complement the first naval air station in the Nicobar group, INS Baaz, meant for aerial surveillance.

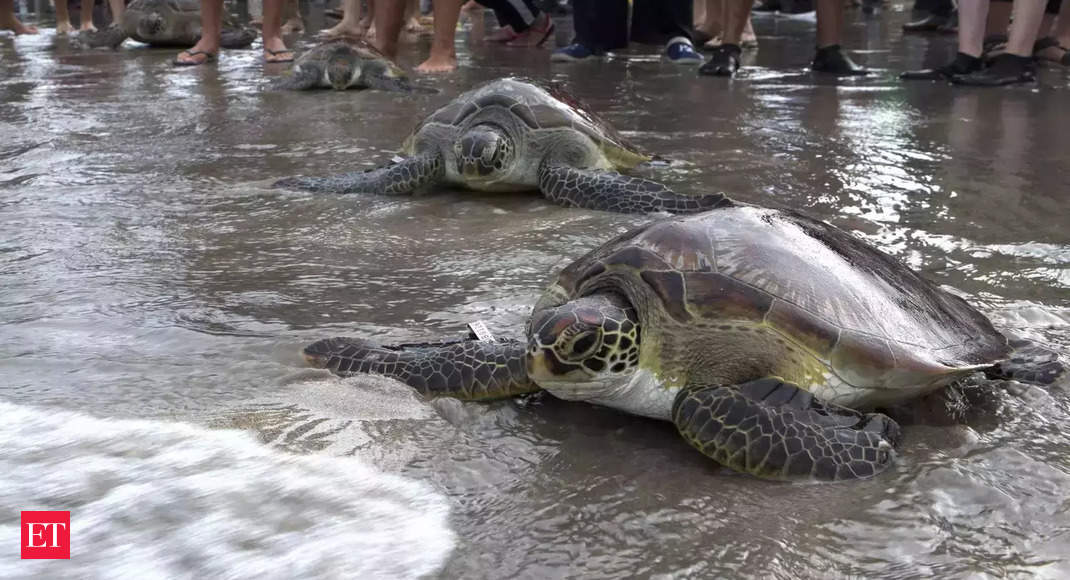

As per the detailed report on environmental clearance, of the four projects, the shipping terminal and power plant would require no resettlement as there are no residents on the proposed site. The greenfield airport site would need relocating 84 people and the township would require very little rehabilitation. “Overall, some 379 families will be directly or indirectly affected by the project,” says a senior MoEF official involved in the project. Great Nicobar has a huge biosphere reserve and is home to rare flora and fauna, including leatherback sea turtles, chicken-like birds called megapodes, the Nicobar macaque and saltwater crocodiles. Swathed in rainforest, the island has two national parks — the Campbell Bay National Park in the north and the Galathea National Park in the south.

While the proposed project is outside the national parks, the site is frequented by Shompens who move seasonally in search of food. “No project activities are envisaged in areas where aboriginal tribes reside. Their lives would not be affected,” adds the MoEF official. While the Shompens are primarily fishers and hunter-gatherers, the Nicobarese depend on fishing, poultry and horticulture for their livelihood. Some also work as daily wagers. MoEF has roped in the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) and the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON) to advise it on the restoration of rainforests and the relocation of corals, leatherback turtles, saltwater crocodiles and megapodes. The ministry’s Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) has also directed the setting up of three independent panels to oversee pollution-related matters, biodiversity and welfare and issues related to the Shompen and Nicobarese tribes. Environmentalists have raised strong objections to the developmental project, pointing to the possible impact it can have on turtles, megapodes, coral reefs and other flora and fauna.

“This project is likely to impact turtles’ and megapodes’ nesting sites and coral reefs. The utmost care must be taken for their preservation,” says an environmentalist who has worked on the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. However, the MoEF official says this gigantic project is the perfect example “to show that development and environmental safeguards can go hand in hand”. Says Dhriti Banerjee, director, ZSI: “We have done an extensive study of the islands. Alternative sites for turtles and corals have been found and they can be translocated, if needed. Coral transplantation is a worldwide solution that could be easily executed on Great Nicobar Island. In the Gulf of Kutch, we have successfully translocated corals.” “Some of the proposed area is part of the habitat of saltwater crocodiles.

If this is classified as Crocodile Conservation Zone, efforts will be made to exclude it from the project. An action plan has been prepared for the mitigation of man-crocodile conflict,” says SP Yadav, director, WII. The project will involve felling trees in 130 sq km of forest land, which is about 15% of the island’s forest cover. The compensatory afforestation will happen far away in Haryana, it is learnt. “The tree cutting-to-forestation ratio is 1:30,” says the MoEF official.

Coral transplantation is a worldwide solution that can be easily executed on Great Nicobar Island”

– DHRITI BANERJEE, Director, Zoological Survey of India

PORT OF CALL

The `35,000 crore transshipment port, which is a key component of the project, could make India part of the global shipping trade and maritime economy, thanks to its proximity to the east-west international shipping route. The tip of the island is hardly 40 nautical miles from a major international sea route in the Great Channel that carries 35% of the global oil supplies and a quarter of the global sea trade.

With no large container transshipment port in India, all international c a r g o g o e s t o Colombo, Singapore or Port Klang in Malaysia. Great Nicobar is strategically located as it is equidistant from these three hubs. “Currently mainline vessels are not coming to India as the draught of (existing) Indian ports is less. Mainline vessels go to Singapore or Malaysia. Owing to its strategic location, the Nicobar port will reduce logistics costs, help in the transshipment of cargo and generate revenues,” says PL Haranadh, chairman, Syama Prasad Mookerjee Port, Kolkata.

He cites the example of Singapore that was once a fishing village and is now the world’s busiest container transshipment port. “Singapore handles 65 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) of transshipment annually and of this 95% is from other countries.” The Great Nicobar port would have a capacity of 14.2 million TEUs.

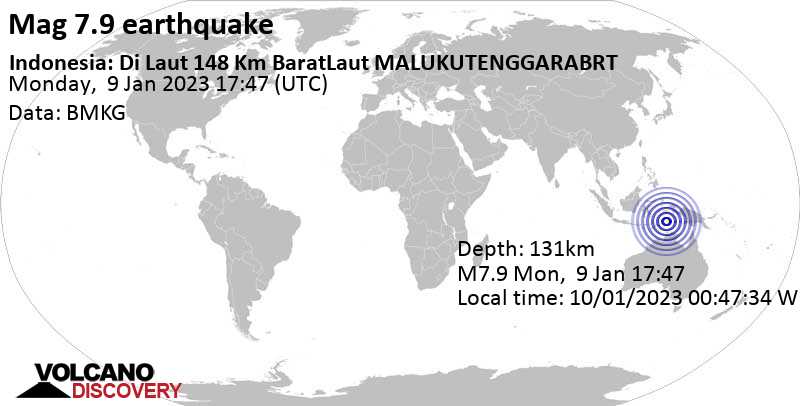

CHINA CHALLENGE

More than anything, experts say, the island is of strategic importance as it allows India to monitor sea lanes in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. It could be part of India’s answer to China’s String of Pearls strategy. Great Nicobar is about 90 km from the tip of Indonesia’s Sumatra island and is strategically located near the Strait of Malacca, a narrow and busy shipping lane that connects Andaman Sea to South China Sea and Indian Ocean to Pacific Ocean. Great Nicobar can be developed as a gateway to Malacca Strait.

This makes the shipping terminal project important from the point of view of defence and national security. According to defence experts, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is important for China for several reasons like energy requirement, trade routes as well as for keeping a check on India. “80% of oil for China comes from IOR. To any Chinese escalation that happens in Galwan, India can give a befitting reply in IOR,” says Srikanth Kondapalli, dean of the School of International Studies & professor of China Studies, JNU.

Great Nicobar may become a docking site for aircraft carriers, sources say. Experts say the development of Great Nicobar from the perspective of national security is a late awakening for India but can hardly be overemphasised. Growing Chinese assertion in the Indo-Pacific region has given great urgency to this initiative. “We are clearly outnumbered by the Chinese in terms of warships or underwater unmanned systems. China is expanding aggressively in the region hence we need to monitor their activities closely.

Though it is a late realisation by India, the mega investment plan is a welcome move,” says Rajiv Nayan, senior research associate, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, Delhi. Even as concerns related to ecology, biodiversity and lives of indigenous communities remain, there is no denying the importance of the project due to its strategic location. “Over 300 Chinese vessels pass through the IOR every day. China has been surveilling India through its ships in the region. We can’t leave such a strategic place as a mere fishing village. That’s why developing the island is crucial above all other concerns,” says Kondapalli.