On the morning of 4th November 2010, a Qantas Airbus A380 suffered an uncontained engine failure, shortly after leaving Singapore Changi Airport. Just minutes into the flight, one of the plane’s engines failed and caused significant damage to the wing and other systems. Against all odds, the pilots guided the heavily damaged superjumbo to the safety of Singapore Changi Airport, averting what could have been a catastrophe.

Flight Details

On November 4, 2010, the Qantas Airbus A380-800 with registration VH-OQA was operating Flight QF32 from London Heathrow to Sydney with a stop in Singapore. However, while heading towards Sydney from Singapore, the A380 suffered an uncontained failure with the number two engine emitting a loud bang. Having entered into service in September 2008, VH-OQA (named Nancy-Bird Walton) is the first A380 delivered to the Australian flag carrier.

Flight QF32 was under the command of Captain Richard Champion De Crespigny who had about 15,140 hours in his logbook, including about 570 hours in the Airbus A380. Captain Richard was accompanied by his first officer, Matt Hicks who had about 11,279 flight hours including about 1,271 hours on type, and second officer, Mark Johnson who had about 8,153 flight hours including about 1,005 hours on type.

Onboard Flight QF32 were two additional check captains, the captain who was being trained as a check captain (CC), and the supervising check captain, who was training the CC. The check captain had over 20,000 hours in his logbook whereas the supervising check captain had over 17,500 flight hours. There were 440 passengers and 26 crew members onboard the aircraft.

After two hours on the ground at Singapore Changi, flight QF32 took off from Changi Airport bound for Sydney. Just 4 minutes after take-off, while the aircraft was climbing through about 7,000 feet, one of the Rolls-Royce Trent 900 engines suffered an uncontained failure. As a result, Debris from the engine struck and damaged the wing and many of the vital systems of the plane causing leaks. During the failure, the flight crew heard two almost coincident ‘loud bangs’, and a number of warnings and cautions were displayed on the electronic centralized aircraft monitor (ECAM).

Following the uncontained failure, Captain Richard immediately selected altitude and heading hold mode on the auto flight system control panel. The crew reported that there was a slight yaw and the aircraft leveled off in accordance with the selection of altitude hold. As the auto thrust system was no longer active, the captain manually retarded the thrust levers to maintain the aircraft’s speed at 250 knots as the aircraft leveled off.

Shortly after, the ECAM displayed a message indicating a Number 2 engine turbine overheat warning and it began displaying multiple messages relating to a number of aircraft system problems. Soon after, the captain confirmed with the other cockpit crew that he had control of the aircraft and instructed the first officer to commence the procedures as presented on the ECAM.

After receiving multiple messages from the ECAM, the flight crew discharged both of the engine’s fire extinguisher bottles one after another. However, they did not receive confirmation that the fire extinguisher bottles had discharged and as a result, they elected to continue the engine failure procedure, which included initiating a process of fuel transfer.

At that time, the engine/warning display indicated that the No. 2 engine had changed to a “failed” mode, whereas the No. 1 and 4 engines had reverted to a “degraded” mode 5 and the No. 3 engine was operating in an “alternate” mode.

Return to Singapore Changi

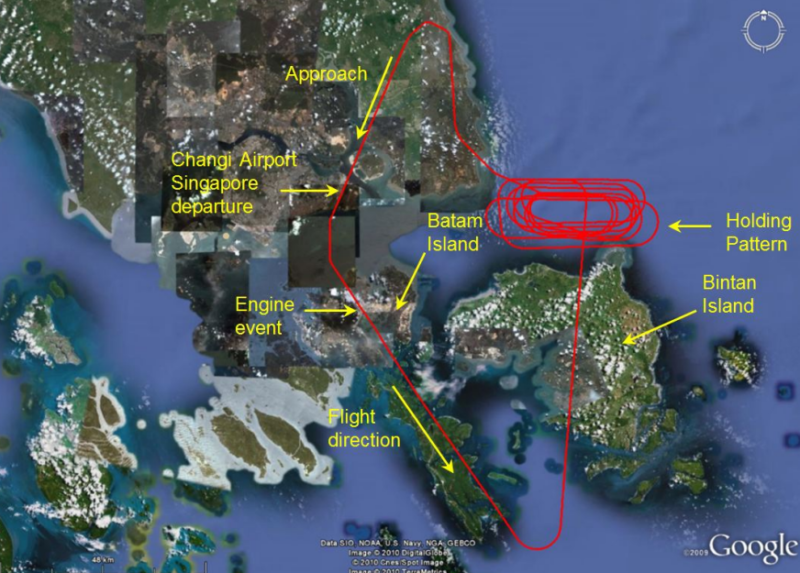

Shortly afterward, while the aircraft was flying over the Batam islands, the crew issued a PAN call to Singapore Approach reporting a possible engine failure. The crew requested to level off at 7500 feet MSL and a heading of about 150 degrees to investigate the occurrence.

About 20 minutes later the crew reported that they had completed an extensive checklist and found a hole in the (inboard) side of engine No. 2 alongside damages to the wing. Before returning to Changi, the crew requested to hold for half an hour. In the meantime, Batam island’s ATC received calls from the ground about debris on the ground and relayed the information to Singapore’s approach controller. Among others, Debris with the Qantas logo fell onto a road in the built-up city district Dutamas of Batam. Some of the debris fell on a school, some houses, and a car in Batam.

After assessing the situation and completing a number of initial response actions, the crew requested an approach to runway 20C at Singapore’s Changi Airport. While in the holding pattern at the east of Changi Airport, the flight crew worked through the procedures relevant to the messages displayed by the ECAM. During that time the flight crew were assisted by additional crew members who were on the flight deck as part of a check and training exercise.

After dumping fuel, the crew initiated an approach to Changi’s runway 20C with open gear doors, retracted slats, and extended flaps. Apart from engine No. 2 all other engines were working normally and the landing was done with flaps configuration 3 due to the slats being unavailable. The A380 eventually landed safely back in Singapore about 2 hours after departure. All those onboard disembarked the aircraft safely. No injuries on board and on the ground in Batam islands were reported.

Shortly, after coming to a stop at the end of the runway the crew requested towing assistance. Responding emergency services found a fuel leak off the left-hand wing, engine No. 2 was found damaged near the rear of the engine, smoke was coming from tire 7 and four tires had deflated. Moreover, the pilots were not able to shut engine No. 1 (outboard left hand) engine down due to wiring damage which prevented the LP and HP valves to be closed. As a result, the fire services foamed engine No. 1 to shut that engine down.

“We’ve got a situation where there is fuel, hot brakes, and an engine that we can’t shut down. And really the safest place was on board the aircraft until such time as things changed,” Supervising Check Captain, David Evans said in an interview.

“We had the cabin crew with an alert phase the whole time ready to evacuate, open doors, and inflate slides at any moment. As time went by, that danger abated, and thankfully, we were lucky enough to get everybody off very calmly and very methodically through one set of stairs.”

David Evans, Supervising Check Captain

Aircraft Damage, Investigation, and Findings

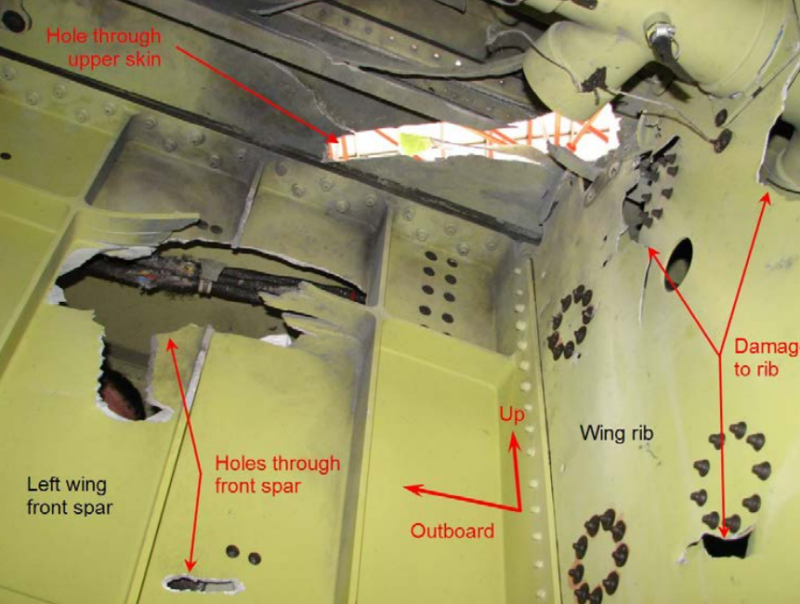

The aircraft sustained substantial damage from a large number of disc fragments and associated debris, which affected the aircraft’s structure and a number of its systems. It was a miracle that the plane was able to land safely at all, let alone with no loss of life. The damage to the plane was extensive, with a hole in the wing and damage to many of the vital systems.

The ATSB found that a large fragment of the turbine disc penetrated the left wing leading edge before passing through the front spar into the left inner fuel tank and exiting through the top skin of the wing. As a result, the fragment caused a short-duration low-intensity flash fire inside the wing fuel tank. It was concluded that the conditions within the tank were not suitable to sustain the fire.

Furthermore, another fire was found to have occurred within the lower cowl of the No. 2 engine as a result of oil leaking into the cowl from the damaged oil supply pipe. The fire lasted for a short time and was self-extinguished. Alongside, the disc fragments severed a wiring loom located between the lower center fuselage and body fairing. That loom included wires that provided redundancy (backup) for some of the systems already affected by the severing of wires in the wing leading edge. As a result, the additional damage to the wiring looms rendered some of those systems inoperative.

The aircraft’s hydraulic and electrical distribution systems were also damaged, which affected other systems not directly impacted by the engine failure. The fact that the pilots were able to keep the plane in the air and land it safely was a testament to their skill and training.

The investigation into the Qantas Flight 32 incident was conducted by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) and involved collaboration with other aviation safety organizations such as the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) and the French BEA (Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la Sécurité de l’Aviation Civile).

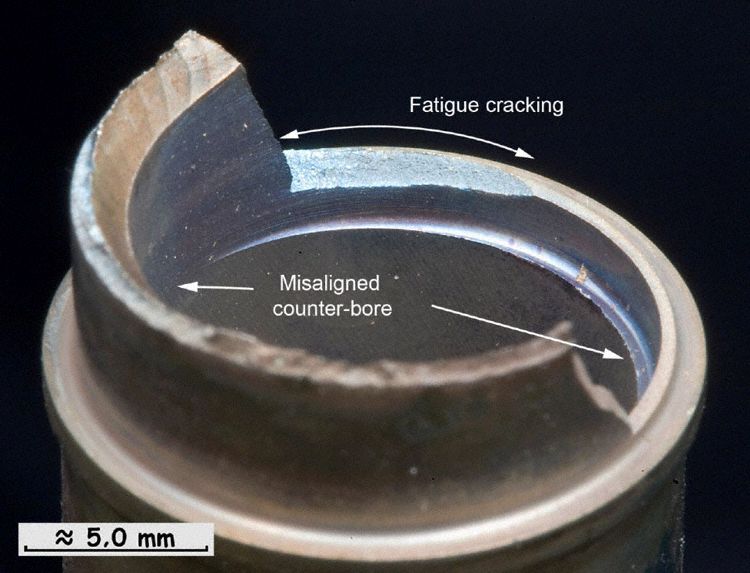

A thorough investigation found that the failure was the result of an internal oil fire within the Rolls-Royce Trent 900 engine that led to the separation of the intermediate pressure turbine disc from its shaft. The fire started when oil was released from a crack in the pipe that supplied oil to the high-pressure/intermediate pressure (HP/IP) turbine-bearing chamber. The ATSB found that the oil pipe cracked because it had a thin wall from a misaligned counter bore that did not conform to the design specification. Additionally, it was found that the engine had not been properly maintained and that the engine’s design did not include adequate protection against oil leaks.

In particular, the Australian aviation watchdog identified a safety issue that affected all Trent 900 series engines in the worldwide fleet. On 1 December 2010, the ATSB issued a safety recommendation to the engine manufacturer to address that issue and published a preliminary investigation report that set out the context for that recommendation.

On 12th November, Rolls Royce released a press statement stating that the examination of the accident engine, as well as the inspection results, permitted Rolls Royce to draw two key conclusions:

- The issue is specific to the Trent 900 engine series.

- The failure was confined to a specific component in the turbine area of the engine. This caused an oil fire, which led to the release of the intermediate-pressure turbine disc.

At that time, the engine maker Rolls-Royce said that it was in the process of checking the 20 A380 planes currently in service – with Qantas, Singapore, and Lufthansa – that use its Trent 900 engines.

Throughout the investigation, the ATSB continued to work with the aircraft and engine manufacturers to ensure that any identified safety issues were addressed and actions are taken to prevent a similar occurrence. The ATSB also identified that this accident represented an opportunity to extend the knowledge base relating to the hazards from uncontained engine rotor failure (UERF) events and to incorporate that knowledge into airframe certification advisory material in order to further minimize the effects of a UERF on future aircraft designs.

Aftermath

Following the event, both Qantas and Singapore Airlines, which use the same Rolls-Royce engine in their A380 fleet, temporarily grounded their A380 fleets for further inspections and repairs. Qantas also launched a lawsuit against Rolls-Royce, which was settled out of court. However, Singapore Airlines A380s resumed operations the following day. Passengers and crew members were shaken by the incident, but grateful to be alive, and many of them credited the pilots with saving their lives.

In terms of aftermath, the airline also made significant changes to its maintenance and safety procedures to ensure that such an incident would not happen again. It also led to an increased focus on maintenance, safety, and design regulations in the aviation industry. The Qantas Flight 32 has been considered a turning point in the aviation industry with respect to safety and maintenance regulations and is often used as a case study in aviation safety training.

The ATSB issued a safety recommendation to the engine manufacturer to address that issue and published a preliminary investigation report that set out the context for that recommendation. As a result, the ATSB issued recommendations to the European Aviation Safety Agency and the United States Federal Aviation Administration, recommending that both organizations review the damage sustained by the aircraft in order to incorporate any lessons learned from this accident into the certification compliance advisory material.

The incident was a reminder of the importance of proper design and testing in the manufacturing of vital equipment and the importance of skilled and well-trained pilots in emergency situations. As a result of the findings, Rolls-Royce was held accountable for the failure and was fined $95 million by the Australian government. The incident also led to increased scrutiny of the Rolls-Royce Trent 900 engine and other similar engines, resulting in the modification and improved maintenance procedures.

Many of the passengers credited the crew members for guiding a heavily damaged double-decker jet to the safety of Singapore Changi Airport and averting what could have been a catastrophe. Moreover, the pilot in command of the aircraft was commended for debriefing the passengers in the passenger terminal after the flight, disclosing details of the flight, and offering care for his passengers.

In conclusion, Qantas Flight 32 was a miraculous event. Additionally, the incident also led to significant changes in the industry, with an increased focus on maintenance, safety, and design regulations.

Feature Image via ATSB